I had Ep 3 all set up for publication when this video popped in my feed. Since Caciocavallo is one of the cheeses I mentioned in the pasta filata section, here’s an annotated thread on what’s going on in this video:

At :19 they talk about the breed used for this particular version of Caciocavallo, the Podolica cow. At 1:37 they mention that the breed gives only 3-6 liters (.75-1.5 gal) per day. By comparison, black & white Holsteins, the source of most North American milk, give 30-40 liters/day.

You might wonder why they would bother with a breed that gives so little milk when they could just get Holsteins–more milk for the buck, so to speak. Some of it is heritage, a belief in preserving local breeds and foodways. Some of it is flavor: different breeds give different proportions of fat and proteins. Holstein milk tends to be “watery” compared to breeds traditionally used for cheesemaking, so it’s not that great for cheesemaking. In addition, different breeds require diff amounts of water, or get along more or less well on different feed types, which make them sometimes better suited to the local environment than breeds from other ecozones. Holsteins & Holstein hybrids have fared quite poorly in India, for example–they get sick a lot.

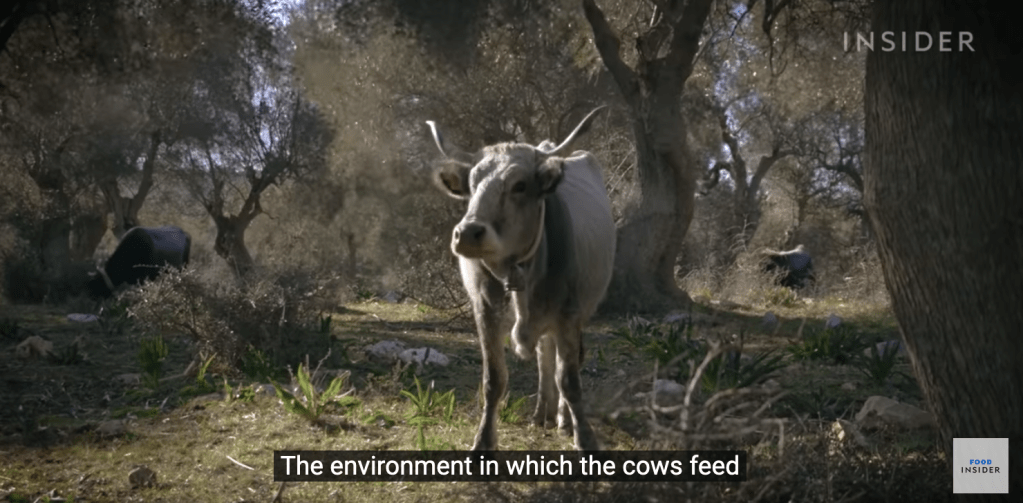

At 1:45 they talk about the environment in which the cows are raised: near sea level, close to the coast, with brackish lakes nearby, and presumably salt-tolerant plants to graze on. We are what we eat, and so are animals–and their milk.

The milk is heated to 40C/104F. Most pasta filata–and many other Italian cheeses–are brought to fairly high temps like this, but Caciocavallo is aged longer than Mozzarella, so it’s heated to a higher temperature. The higher heat helps the acid develop more quickly, but there are other reasons to use the higher heat: thermophilic cultures (the one that like higher heat) tend to be more active in the finished curd for longer, so they help maintain consistent rate of fat and protein breakdown over time. And during the make, the higher heat causes the proteins in the curd to tighten more and expel more of the whey. So the curd is drier to begin with, which also allows it to age longer.

At 2:10, the cheesemaker adds rennet & whey from the previous day together to the milk. The whey contains cultures & acid, so it’s what kicks off the fermentation process. This is the traditional way (heh) cheese was made, before the development of freeze-dried cultures.

It also makes for more variability in the cheese esp between seasons: when it’s cooler, the whey won’t be as acidic, certain cultures may be less active, etc.

With many cheeses, you add the culture solution first, wait for a while, then add the rennet. The rennet slows down the fermentation. But in the approach shown in this video, the curd is going to spend a long time developing the right acid levels AFTER the curd is cut so it makes more sense to coagulate the milk relatively quickly, and then cut it.

At 2:15 we’re introduced to the cutting instrument, the menaturo:

It’s quite unlike the metal cheese harps used elsewhere, which cut the curd into nice even blocks. Here, the goal is to cut the curd into very small pieces, so he basically beats it apart.

Notice that it’s made out of wood. And so’s the vat that they move the curd to for ripening. Wood is a wonderfully porous material that absorbs all kinds of local yeasts and cultures to help reinforce what’s already been introduced with the whey.

While the curd sits in the warm whey, it continues to acidify, which is really important in pasta filata cheeses. Fresh milk has a pH of ~6.6. When the curd goes into the warm vat of whey, it’s usually ~6.0. It reaches stretchability between 5.3-5.1. Here’s a nice blog on the subject of acid and stretchiness in cheese if you want to dive further into that.

Once the curd has reached the right pH level, it’s cut into strips to get it ready for stretching. NB. Because it’s stretched at such a high temp (100C/212F!), the curd is pasteurized during the stretching process.

But the USDA doesn’t see it that way: because most caciocavallo in the US is served young, they insist the milk has to be pasteurized prior to cheese manufacture. This does impact the strength of the proteins and ultimately the stretch of the cheese….

Back at 4:22 they talked about the yellowish color of the curd, and the fact that it comes from the milk and what the cows eat. I talked about yellowness a bit in this post: tl;dr some cow breeds retain more of the beta-carotene from grass than others. The hue is also retained in the milkfat, so more fat, more yellow.

Finally, at 8:02, the cheesemaker talks about hanging the cheeses from his “lucky tree”.

It’s not just magical thinking: the surfaces of the cheese get turned without human help and dry quickly thanks to the slightly salty sea breeze. And also the cheese gets an extra dose of local yeasts and other microfauna for that extra terroir before it settles into the cave for aging.

Originally tweeted by IntoTheCurdverse (@curdverse) on April 3, 2022.

Pingback: Ep 18: Ohhh, Biiiiig Stretch! | Into The Curdverse