I have a real dislike of the phrase “aged like milk” when used to indicate something aged poorly. Because aging milk is what produces interesting, complex cheese. Not all cheeses are aged, of course, and there’s something to be said for cheeses that showcase the sweet creaminess of fresh milk and pasture. But as a means of storing complete proteins for use in times of year when fresh foods are less available, it’s hard to grow wrong with cheese.

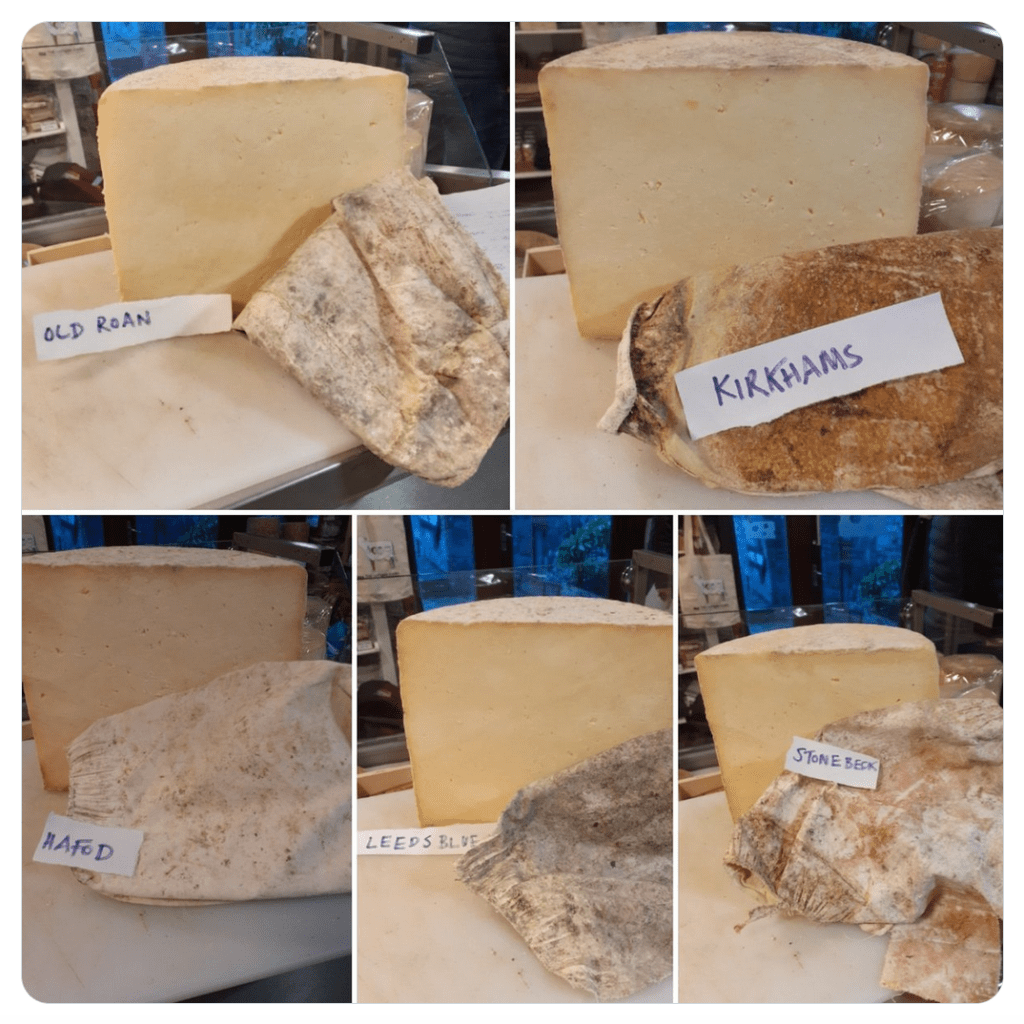

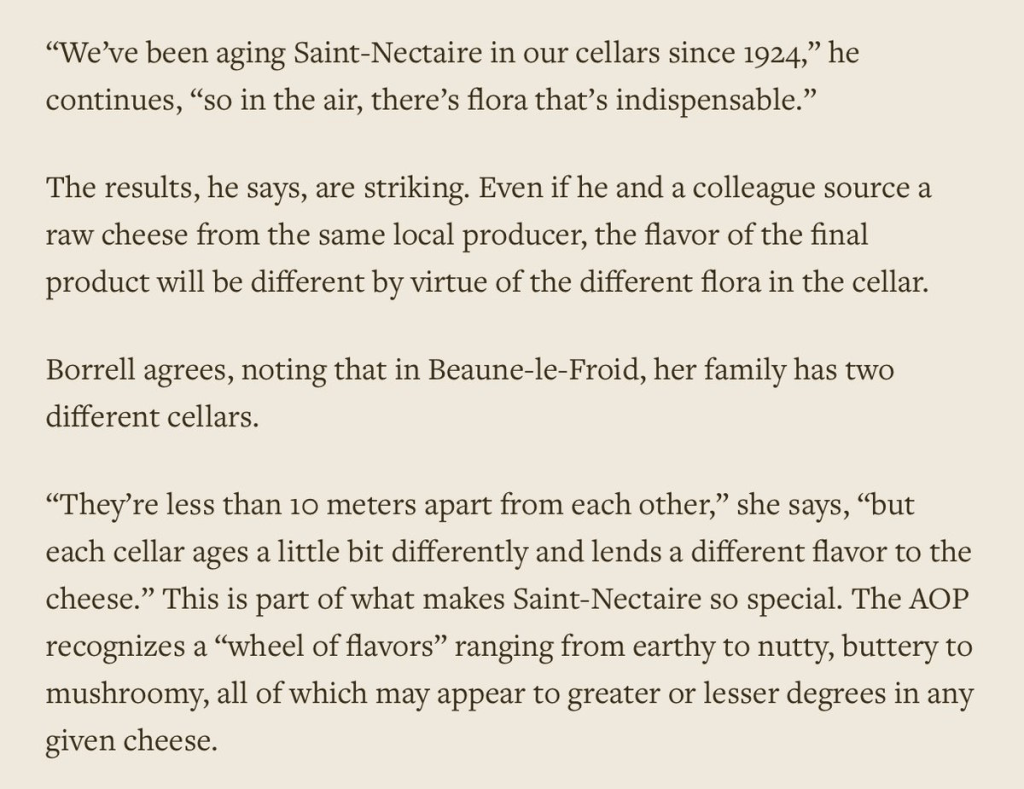

How the cheese is stored makes all the difference in the ultimate flavor of the cheese, and even its texture. Here are several cheeses, all of the same type, from the same dairy, which were sent out to several different aging facilities.

The grey/brown things in front of the cheeses are the bandage wrappings that they aged in. As you can see, in different spaces, they grew different types of molds — and some have more mold, others less.

You can read about the variations in flavor and texture between these separated-at-birth twins in this Twitter thread.

Leaving aside the cheeses that are essentially desiccated and kept away from moisture–common in the more arid regions in the world–aging a cheese is an ongoing dance of managing the microbial environment in which the cheese lives and breathes on its way to maturity. Different cheese types require different environments: some like things slightly warmer, others a bit cooler. Sometimes a cheese will spend a few weeks in a warmer space to develop certain yeasts and molds, and then move to a cooler one to allow the interior to ripen slowly. Surface-ripened cheeses such as bloomies and washed rinds tend to want more humid environments–95% humidity is common–while natural rinds do better at ~85% humidity. Temperature and humidity are two key variables that affect which microbes, yeasts and molds will be thriving in the air in the aging space, how effectively they may colonize the surface of the cheese, and even which ones will be able to develop within the curd itself.

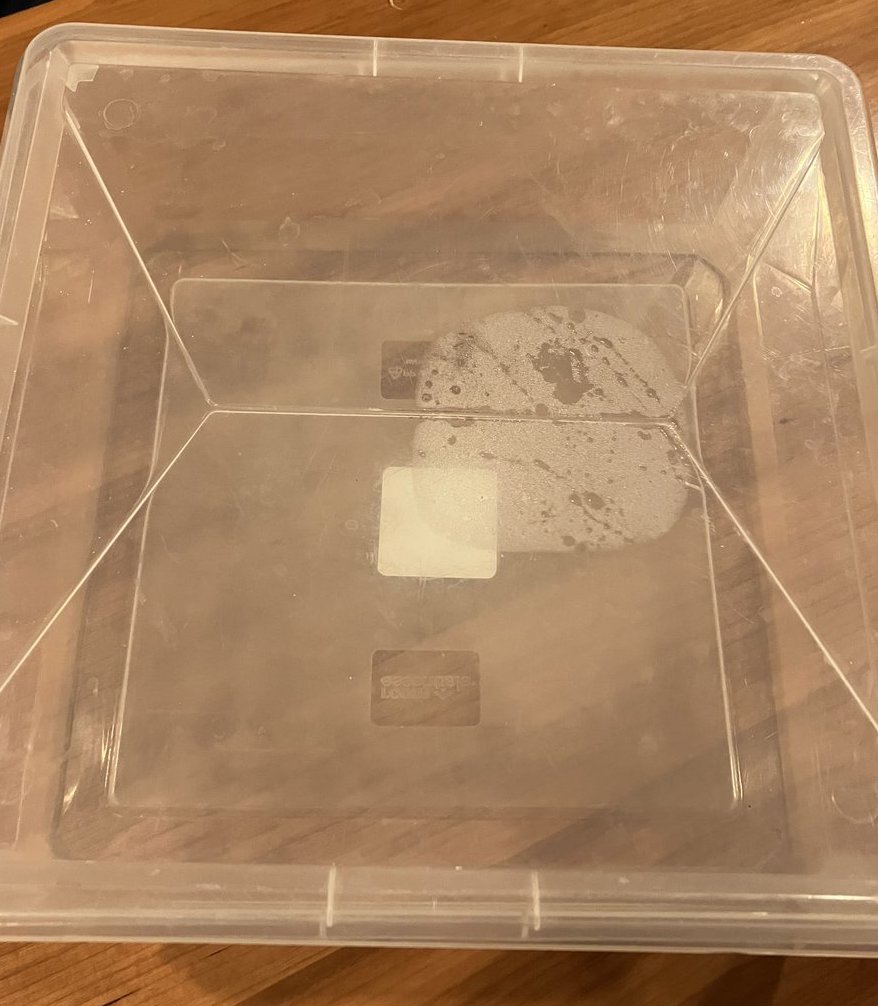

The other part of affinage–that’s the art and science of aging cheese to perfection–is hands-on human intervention. Cheeses breathe. The younger they are, the more moisture they exude. Here, for example, is a box in which a brand-new cheese had been sitting overnight, lid slightly ajar. Guess where the cheese was sitting within the box?

In this week’s Episode 15 (out on Friday), affineur Perry Wakeman talks a lot about turning cheeses, because flipping large English-type cheeses–anywhere between 10-50 pounds–is hard work. And as you can see, the side that’s facing up gives off a lot of moisture. The bottom side tries to as well, but doesn’t have the airflow that the top does–so depending on what sort of shelving it’s sitting on, the bottom side can get moldy or slimy if left too long in one place. So cheeses need to be turned regularly to ensure even moisture throughout the cheese, and an even rind. There’s quite a lot of attention paid to the rind and managing what’s growing on it, as well.

The aging space is most often referred to in European-style cheesemaking as “the cave”, because the sedentary peoples in western Eurasia have long made use of natural caves for storing and slowly aging a variety of foods: cheese, wine, olive oil, cured meats, etc. (No big surprise that these foods tend to all show up together in the cuisines of people who make them.) Natural caves offer cool, relatively consistent temperatures and high humidity, which turn out to be just the sort of conditions cheese cultures like best. Of course, there are only so many caves available, and in some regions there are more than others. And they can be homes to a variety of other non-microbial beasts as well, which tends to give modern food regulators pause. So thanks to modern refrigeration technology, plenty of affinage is done in purpose-built warehouses today.

When a cheese ages, the cultures that are in the milk are always interacting with those in the surrounding air, so that surrounding microbiome is critical. A human-built cave is somewhat easier to clean than a natural one: perhaps too easy–if you clean your cave too thoroughly, you lose the microbiome that has been built up in the cave by successive generations of the cheese that have inhabited it. But even in built caves, as Perry describes, some surprising things can happen.

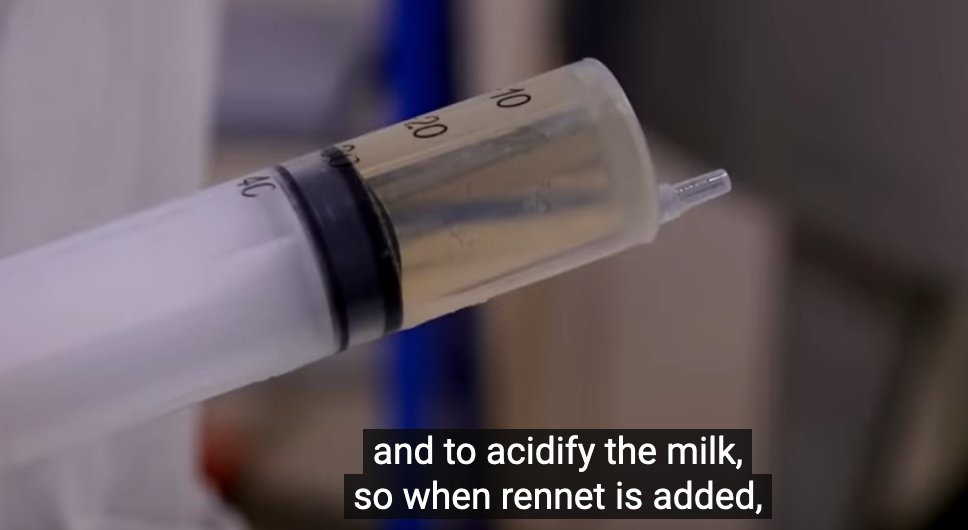

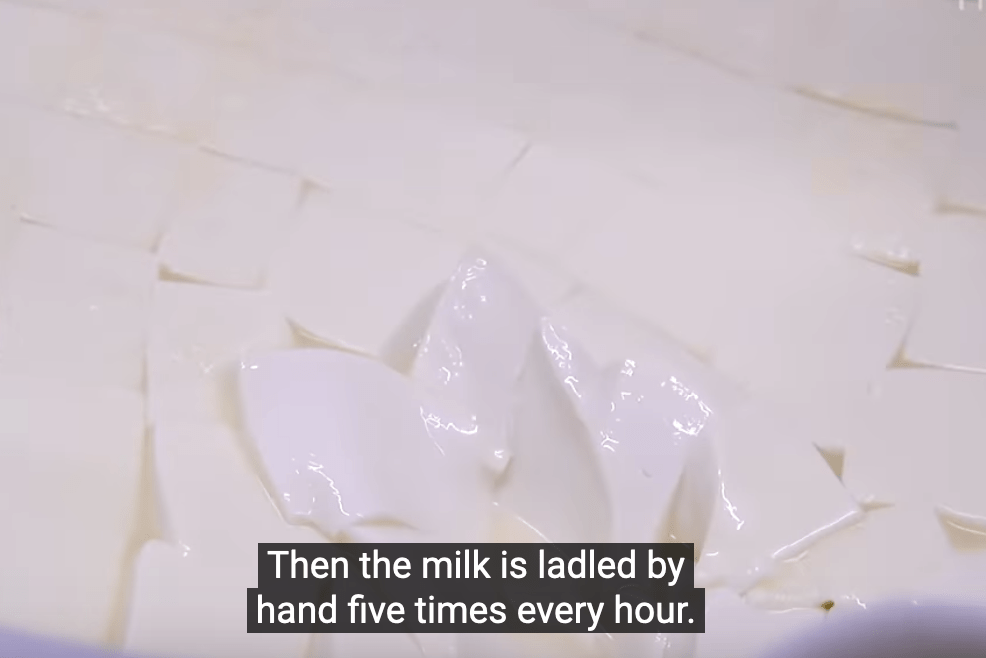

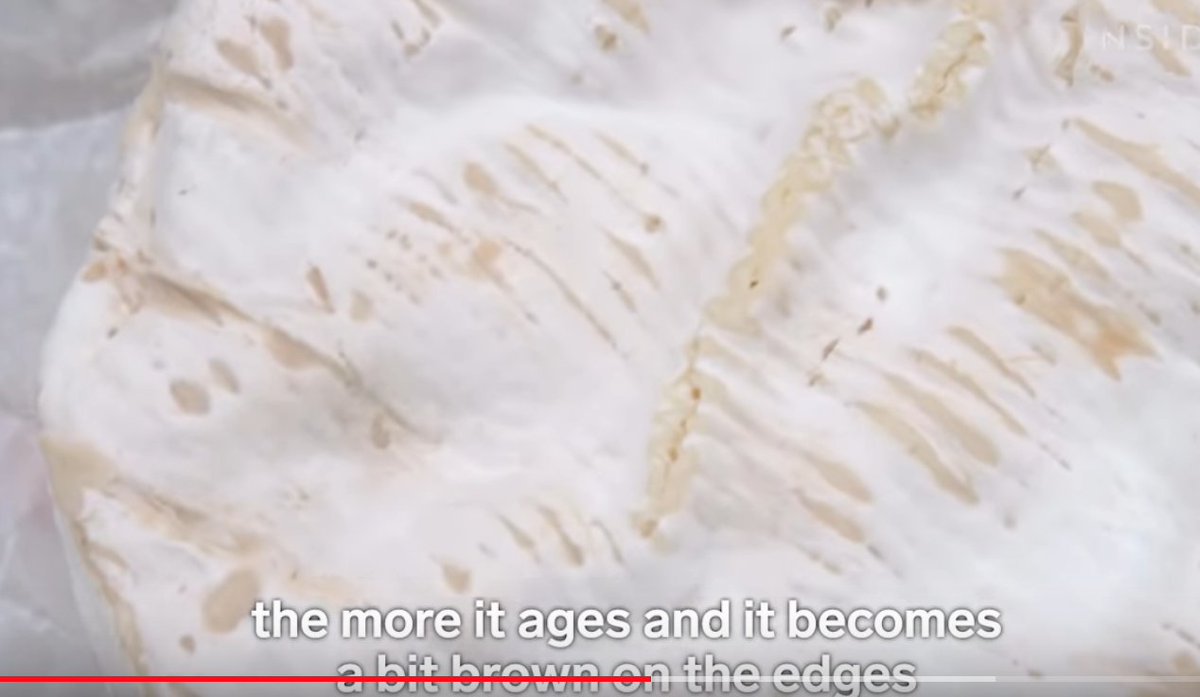

The microbiome of natural caves can be exponentially more complex. I was completely sold on the natural cave effect when we visited the Cheddar Gorge in Somerset, England several years back: they usefully provide very clear-cut A/B testing. =) Cheesemaking had actually died out in the gorge in the mid 20th century, but a new creamery opened there in 2003. The gorge is pockmarked with numerous natural caves. In fact, this is the site of Gough’s Cave, where the mesolithic Cheddar Man, as well as some earlier humans, were buried, 9-14,000 years ago. (They all lived before domesticated ruminants arrived in England–no cheese for them.) When we visited in 2007, the creamery had just gotten permission to age cheese in Gough’s Cave a few months prior. And WOW. I’m not generally a huge fan of cheddar; I don’t like it sharp for the sake of sharpness, and often find it rather “one note”. But! The cave-aged cheddar is nothing like even the same creamery’s “modern-aged” cheeses, even with all other inputs being the same. It’s slightly crumbly, but still creamy, with a huge variety of flavors and just a slight sharpness at the end to cleanse the palate. There’s a nice video that shows the whole cheesemaking process they use, including what the cave-aged cheeses look like in comparison with the standard version. You see the beginning of the affinage process at 4:45, and then at 6:04 you’ll see the texture difference between the cave-aged and the “vintage” storeroom-aged versions.

In fact, two caves in the same valley or hillside can have notably different microbiomes. Here’s an excerpt from great article about the mix of natural and artificial caves used in the production of Saint-Nectaire, a washed rind cheese from south-central France:

Another article about a cave in Transylvania (complete with a greedy count!) talks about the particular strains of B Linens native to that cave which are responsible for the particular flavors of Năsal cheese.

One of the things Perry and I got into a bit is the evolving nature of the business of affinage. Traditionally, cheese producers aged their own goods in caves or cellars they owned. This was true of small farmstead producers, as well as the large estates and abbeys who produced cheeses in large quantities. Urban cheesemongers would have appropriately cool and humid storage facilities, but expected to receive nearly finished cheeses, banking on fast turnover in order to keep their stock levels manageable. Now, affineurs are becoming important middleman businesses, both aging cheeses that they receive shortly after their production in specially optimized facilities, and acting as distributors for those cheeses.

There’s lots more to learn about affinage in Episode 15. Perry’s love of his craft is incredibly infectious, and his answer to my final question was very moving. I hope you enjoy the interview.