About six weeks ago, I started a Montasio, a mountain cheese from the Veneto-Friuli region of NE Italy.

I’d made it before, a very long time ago, and found it uninteresting, so I didn’t make it again. But! I came back to it last month because of a somewhat unusual finishing technique it sometimes receives: it’s coated with a few layers of honey in the early stages of aging. And I got this really interesting desert wildflower honey when I was in New Mexico that I thought would be great with the slightly nutty flavor of this cheese.

Let me explain about the honey.

There are a number of long-aging cheeses where you oil the rind, creating an anaerobic barrier between the actual cheese surface and the surrounding air to help ward off molds.

Honey does the same, but it's got some even more interesting things going on:

Honey is pretty acidic. Actual pH varies quite a bit, but average in the upper 3s and low 4s. That makes for a pretty unfriendly surface for acid-sensitive microbes, yeasts and molds, of which there are many. You may have heard of honey being used on diabetics’ foot injuries; the combo of oozy spreadability (easy to get into small nooks and crannies)the acidity, and the anaerobic nature of the substance all make it a great way to seal off wounds from harmful microbes.

Now here’s the interesting thing about honey-rubbed Montasio: the first records of it come from a Benedictine monastery in the 13th c. That’s not to say that it didn’t exist before then, by any means. But it’s often aged for a really long time, and especially before the modern era, the people who had the real estate to age things for months or years, in the forms of caves & cellars, were the nobility and the Church. It’s why certain monastic orders are known for wine, cheese and beer: these were major sources of income for monasteries, which were often expected to be financially self-sufficient.

Honey, prior to the introduction of sugar cane & refined sugar from the Islamic world in the late middle ages, was pretty much the only source of sweetness in Europe. And it was a luxury item.

So guess what another major source of income for large manorial & monastic estates was? Honey.

So our Benedictine friends in NE Italy evidently had not only livestock, but also beehives. You can absolutely age Montasio without honey–oiling it, for example. But you might imagine that just like any modern enterprise, they may have had several different models in their product line, and the honey-rubbed version may have been the top of the line.

Some sources I've read also say Montasio was originally a sheep-milk cheese, or sometimes mixed-milk, but commercial versions I've seen, at least in the US, are all cow milk. So I'm making cow today. I may make it again with sheep milk some other time.

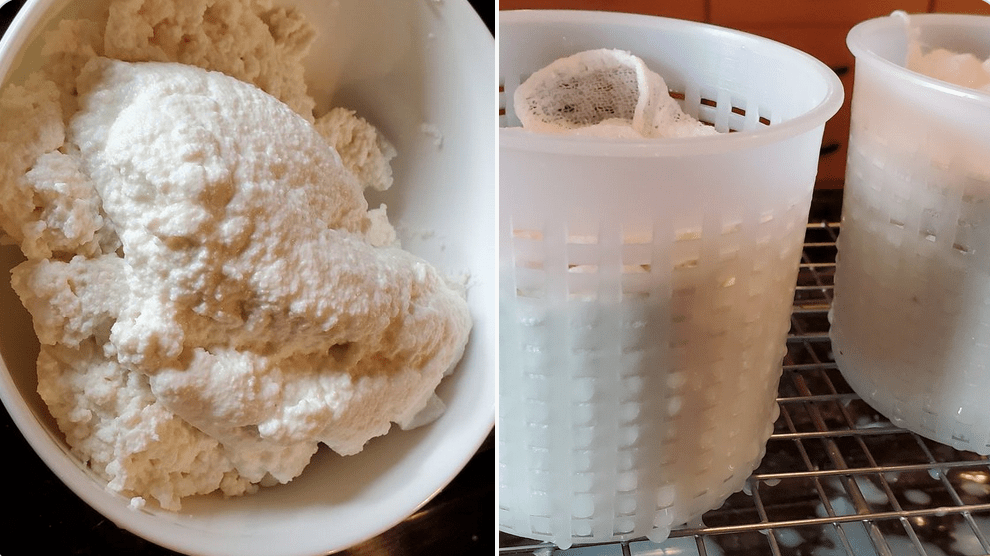

This is a fairly straightforward thermophilic cheese: heat the milk to 95F, add cultures, let them “ripen” or acidify the milk for 30 minutes, then add rennet and let it coagulate for another 30 minutes.

Also as it common with thermophilic cheeses, because you want to let a lot of the whey out, you cut the curd pretty small, .5cm. Then you cook them some more by slowly heating them to 110F over 30 mins, stirring slowly all the while.

After that, I turned off the heat and let the curds sit in the hot whey for another 30 mins, stirring every few mins, until the outsides were quite dry and not sticking to each other, and the individual curds were quite springy instead of squishy. Rubber band consistency.

Once the curds are cooked to the right consistency, you drain them and then press at about 20 lbs for an hour. Then lip the disc and press them for another 30 mins at 30-35 lbs, keeping them reasonably warm, 75-80 F, while they knit. The heat helps with the knitting process. The final weight of ~45 lbs stays on overnight.

Two other recipes for Montasio I have call for salting the curds before you put them into the press, which largely stops acidification. This one acidified for basically 18 hrs before I brined it the following morning.

Those other recipes also use 4-8x as much culture as this one. 🙂 So this is the very definition of low & slow fermentation. I’ve been liking the results of the low & slow approach better, which is why I opted for this one.

This is the baby Montasio just after being turned in its brine; it was there for a total of ~8 hrs. The final cheese is a bit salty, so I might do it for a shorter period of time next time.

After a couple of weeks of aging in the cave, the rind is fairly solid but not yet growing mold. That’s when the honey went on, 3 coats in all, drying for a day or so in between.

The honey is one I picked up on a trip to New Mexico. The Santa Fe Honey company is run by an extended family who has some 200 hives around the state. The majority are in the Rio Grande Valley, but some (like this one) are from the high desert and mountains. It’s got a dark caramel flavor with a hint of sage.

After a total of 6 weeks of aging, I can say that this Montasio is definitely better than the other ones I’ve made—mostly due to the milk, I think.

The last two I made were with standard supermarket milk and had that one-note sharpness of a lot of mass-market harder cheeses. This one is from raw Jersey/Brown Swiss milk, and has a richer, more buttery flavor. The honey on the rind isn’t really noticeable on its own, but if you eat slowly you get hints of the dark caramel along with the butter. It’s a fairly salty cheese, more than it is a sharp one.

Adding a dab of that same desert honey on a slice of the cheese makes all the flavors really bloom.