This is a replay of last year’s Cheeses of the Season: Spring episode. Check out the episode notes here.

This is a replay of last year’s Cheeses of the Season: Spring episode. Check out the episode notes here.

Episode 13 talked a lot about Cheddar and its classic milled cousins. We left the story just hinting at the ongoing renaissance in British cheesemaking. In this episode, I interview passionate cheese nerd Mike Nistor (Instagram | Twitter) about how British cheeses are evolving–and some of his favorites and where to find them.

Cheeses Mentioned

Trethowen Brothers Pitchfork Cheddar and Caerphilly

Cheesemakers of Canterbury Ashmore Farmhouse and Dargate Dumpy

Kingstone Dairy Rollright and Ashcombe

In Ep 13 on Cheddar, I mentioned bandage wrapping a few times in passing, but I found out from Twitter discussions that there are plenty of folks who are unfamiliar with the technique, since it’s something one only very rarely sees on package labels, and even then, there’s nothing resembling a “bandage” in evidence when you buy that piece of cheese.

With bandage-wrapping, you sort of make a mummy of your cheese: smear a layer of fat on the rind–originally whey butter, then later suet, now some folks use vegetarian options like palm or even Crisco. I like to use bacon grease, as it’s something we always have a lot of and it adds a wonderful, subtle, smoky flavor to the cheese. Then add a layer of cheesecloth and press it into the fat. Repeat two to three times more.

If you’re familiar with confit, you’re probably aware that fat can be used to seal off meat from oxygen and unwanted microbes that might otherwise grow on the surface of the meat. It’s the same principle here. The layers of cheesecloth make it easier to apply additional layers of fat since that’s harder to apply thickly on a freestanding thing like a cheese, vs meat that’s placed in a crock and surrounded w/liquid fat. The cloth is breathable, so it allows for some passage of air & moisture (waxed cheeses get much less), but cloth & fat combo greatly limits the exchange. That in turn limits how thick the rind of the cheese gets, which is important in a cheese that will age for a long time: you get more edible cheese if you don’t have a thick, dry rind. At the same time, it slows the surface aging, while allowing the interior to ripen slowly.

You don’t get as thick and dry a rind because less moisture is able to evaporate through all that coating. And that’s important in regions where the climate is relatively dry–especially if it’s also warm–because it prevents the rind from cracking. Cracks in your rind let in molds and sometimes also insects, if you’re an 18th or 19th century cheesemaker aging your cheeses in a barn or cellar. And those are bad news.

Cracking is less likely to happen if the cheese is almost evenly dry all the way through–think of the really hard cheeses from warm, dry climates like Parmesan or Pecorino. But Cheddar was designed to be a softer, moister, more toothsome cheese–and it was originally designed for shipping in the cool, damp climate of the North Atlantic. But New England gets hotter and drier in summer and colder and drier in winter than Britain–and already in the 1700s New England cheesemakers were shipping their wares to the much hotter climes of the mainland southern colonies as well as the British colonies of the Caribbean. So protecting the rind was critically important.

By contrast, you don’t get cracking if the cheese is kept in a cool, humid place–but you do get mold growth. And this is the other big attraction of bandage-wrapping: it limits mold growth on the rind of the cheese. So bandage wrapping has advantages no matter what sort of climate your cheese finds itself in.

Many types of cheese make a virtue of mold, with cheesemakers encouraging certain types of molds and erasing others. The yeasts and molds on a rind get their sustenance from the cheese itself, and as they process those cheese nutrients, they also contribute to the slow breakdown of fat and protein in the cheese, which changes the texture, and also produces various esters and ketones that provide more complex flavors and odors to the cheese.

A skilled affineur, or cheese ager, knows how to develop and maintain a certain mold profile on a consistent basis. But still, these are wild, living organisms; the composition of the milk and therefore the organisms’ diet changes through the seasons; and there’s always subtle variation due to a variety of factors.

Subtle variation is the mark of a well-made artisan cheese. Wild, not-well-controlled variability is a manufacturing problem. And because skilled affineurs and just-right aging environments are somewhat rare and expensive, not having to carefully tend a rind is a big advantage in making an affordable product at scale–which was the primary goal of cheddarmakers almost from the very beginning.

This picture is courtesy of the head affineur at Rennet and Rind, a British affinage house. It’s a fantastic closeup of a bandage-wrapped cheese. But all that grotty-looking mold on the bandages…pretty much stays on the bandages. When you peel them off at the end of aging, you’ll have little to no mold on the thin rind, and a very clean-looking cheese.

Originally tweeted by IntoTheCurdverse (@curdverse) on February 6, 2023.

Cheddar is one of the most widely sold cheeses in the world. It’s made in every hemisphere, and is a central ingredient in countless casseroles and other cheesy dishes throughout the Anglosphere.

Its signature tang and unusual size and shape are all products of a quest for the perfect balance between a crowd-pleasing, snackable texture and durability.

Its history encompasses trade wars, conquest and empire, and the birth of industrial-scale food production, as well as international cooperation in the development of dairy science.

Dive in with the first episode of Season 2, and don’t miss the continuation of the story in Episode 14!

(Re) sources

Ep 2: A Leap Towards Immortality

How a 3,930 Pound Cheese Helped Union Army Soldiers During the Civil War

Credits

Photo: Wookey Hole Cave Aged Cheddar

Battle Hymn of the Republic – US Air Force Band

There’s an old tale going around a lot this week, in which shepherds abiding in fields keep watch over their flocks by night. Very old tale: humans have been doing that for some 11-13,000 yrs, first for meat, then wool, then milk. The only animals w/whom we have an older domestic relationship are dogs.

You know where this is going…cheese. Yogurt is part of this thread too, since it’s what inspired a lovely article (to follow) which explores dairy in Eastern Turkey–the westernmost part of the Fertile Crescent region where domesticated sheep were developed. It’s about the hometown of Hamdi Ulukaya, the rags-to-riches founder of Chobani yogurt. In his hometown, of course, yogurt is made from whole sheep milk. so ~8% milk fat. Rather different from what’s Chobani makes in the US.

You really should read the whole article, if only to travel to someplace you may never go, and read about things that may soon disappear: notably the local cheese, which has been made pretty much the same way for millennia. But there are a few passages I wanted to highlight.

First, the fact that milk is actually a seasonal product, just like cherries & tomatoes. I’ve highlighted that in each of the Cheeses of the Seasons episodes, but it’s quite easy to forget for urban dwellers for whom milk is always just there, seemingly always the same. The authors of the article were unaware of that before visiting the town. =)

Cows lactation cycle is quite long, typically ~300 days, and modern domesticated cows are not strongly seasonal breeders, with both reproduction and milk production being a matter of nutrition–this is partly why in cow-centric countries, milk seems eternally available. Sheep and goats are much more strongly seasonal, like their wild counterparts, and while modern science has made it possible to manipulate these cycles somewhat, their lactation cycles usually run 6-8 months for dairy breeds, less for non-dairy breeds.

Natural reproduction cycles for sheep and goats align very closely to natural feed availability. If you or your partner have ever nursed a baby, you know that milk output is minimal for the first 2-3 months, then kicks into high gear and mom is ravenous. Same for dairy animals. Babies are born in early spring; early milk production is powered primarily from mom’s own fat stores, augmented w/dried fodder and the first fresh grass. Just as babies start getting really hungry, pastures are full of mature grass. In the fall, as grasses dry and die, herds are traditionally culled, babies weaned and everyone goes on dry fodder again. Moms’ teats get a rest, and the cycle starts again. This brings us to a traditional method of cheese production: cheeses are made in-pasture, right after milking. In Europe, this in-pasture style of cheesemaking is called “alpage”, a designation you’ll see on some gruyere & other alpine cheeses.

The milk is heated a bit during the cheesemaking process, but only some are heated to high enough temps to be counted as pasteurized. Most are raw milk. And here we come to conflicts between traditions and modern regulations.

You’ll notice, in the above quote, another common element of dairying: gendered tasks. In western Eurasia, it’s common for men to look after live animals and for women to process the milk. So much so that cheesemaking and witchcraft–another heavily gendered activity–have long been linked in western folklore…

About that goatskin in the previous quote: the local cheese, “tulum”, was traditionally aged not in caves but in animal-skin bags, which are much handier when you’re doing alpage cheeses while moving about in the mountains. Like any skin, they’re somewhat porous, allowing excess moisture to escape the curds and a regular flow of air to reach them. No doubt the authorities will have problems w/that too, even if the pasteurization issue gets resolved.

But there’s one more problem: that part about watching over their flocks by night:

Sheep have changed a lot in the millennia since humans started rounding up mountain sheep–their shape, their size, how much wool and milk they produce. But their natural cycles–and those of their predators–have not. And our natural biorhythms haven’t either. In an era when there are many ways to earn a living that don’t involve staying up all night outside in the cold, human preferences tend to win. Back 2000+ yrs ago, when animals meant livelihood, even wealth, the sacrifice of a lamb to unseen powers was significant. It’s why it was embedded in rituals of many West Asian religions.

We’ve now mostly given up that form of sacrifice in the West, but you can still appreciate the work of all those shepherds, ancient and modern: if you’re thinking in terms of lambs this week consider partaking of some of their cheese. Here are a few suggestions to get you started:

Best Cheeses 2019: Sheep’s Milk – culture: the word on cheese

When I first arrived in France in my youth and was presented with a wedge of brie after dinner, I did what most Americans do: I cut off the tip. And was promptly admonished. You’re supposed to cut along the side, getting a very thin wedge for yourself so that everyone else partaking of the cheese can do same, everyone getting an equal amount of rind & paste. At the time, it was explained to me as politesse.

I was reminded of that moment when this popped up in my Twitter feed the other day:

There it was, my long-ago crime, compounded many times over by many different people and splashed across the internet. (I did, in fact, confess to my own commission of this crime on Twitter a couple of years ago.)

Let’s dissect this particular crime scene for a moment: the board contains 3 types of cheese, a white bloomy rind, a semi-firm cheese (the one cut into sticks that look like French fries if you’re not looking closely), and a blue cheese. This is a common number and the usual assortment of cheese types.

Two of these cheeses, the bloomy and the blue, are mold-ripened cheeses. The bloomy ripens from the outside in (cf Ep 7); the blue, at least as far as the blueing is concerned, from the inside out (Ep 8). So if you cut off the tip, you’ll get either the most (for the blue) or the least (for the bloomy) ripe part of the cheese, while everyone after you gets progressively riper or less blue portions and more rind . And the rind itself contributes flavor & texture, so ideally you want to experience it in a consistent ratio to the interior. Thus the desire to have everyone cut themselves a small slice from the side, allowing equal portions of interior (the paste) and the rind for everyone.

In general, you won’t go wrong doing that with any kind of cheese. But then why is the other cheese pre-cut in matchsticks? This was a catered event, not a private gathering, and you don’t want everyone who comes along wrestling to cut from a large, hard wheel of cheese. It breaks the flow of the food line. So you might as well pre-cut a hard cheese that won’t stick to the board at room temperature (unlike a well-made bloomy), especially since food waste is calculated into the catering budget. The cut pieces will dry out slightly, having been cut in advance, but harder cheeses are basically pretty stable at room temperature for long periods of time. This particular cheese is in matchsticks because the source wheel is fairly large and tall. So the prep staff cut out thin wedges, and cut each wedge across (just a little bit of rind on each end for everyone), and discarded the very thin end and the thick outer edge in the back.

Once you understand the basic principle here — complete, balanced taste and texture for yourself with each piece of cheese, and the same for everyone else — any other seemingly arbitrary rules about cutting cheese should start to make sense.

That said, there’s an excellent video by the late Anne Saxelby that delves a bit further into the different cheese types, and does a great job of explaining the nuances and reasons for cutting a cheese one way vs another. It’s also a very soothing way to while away a bit of a lazy weekend afternoon or evening. If you’re short on time, though, skip down below the video for a few words about knives.

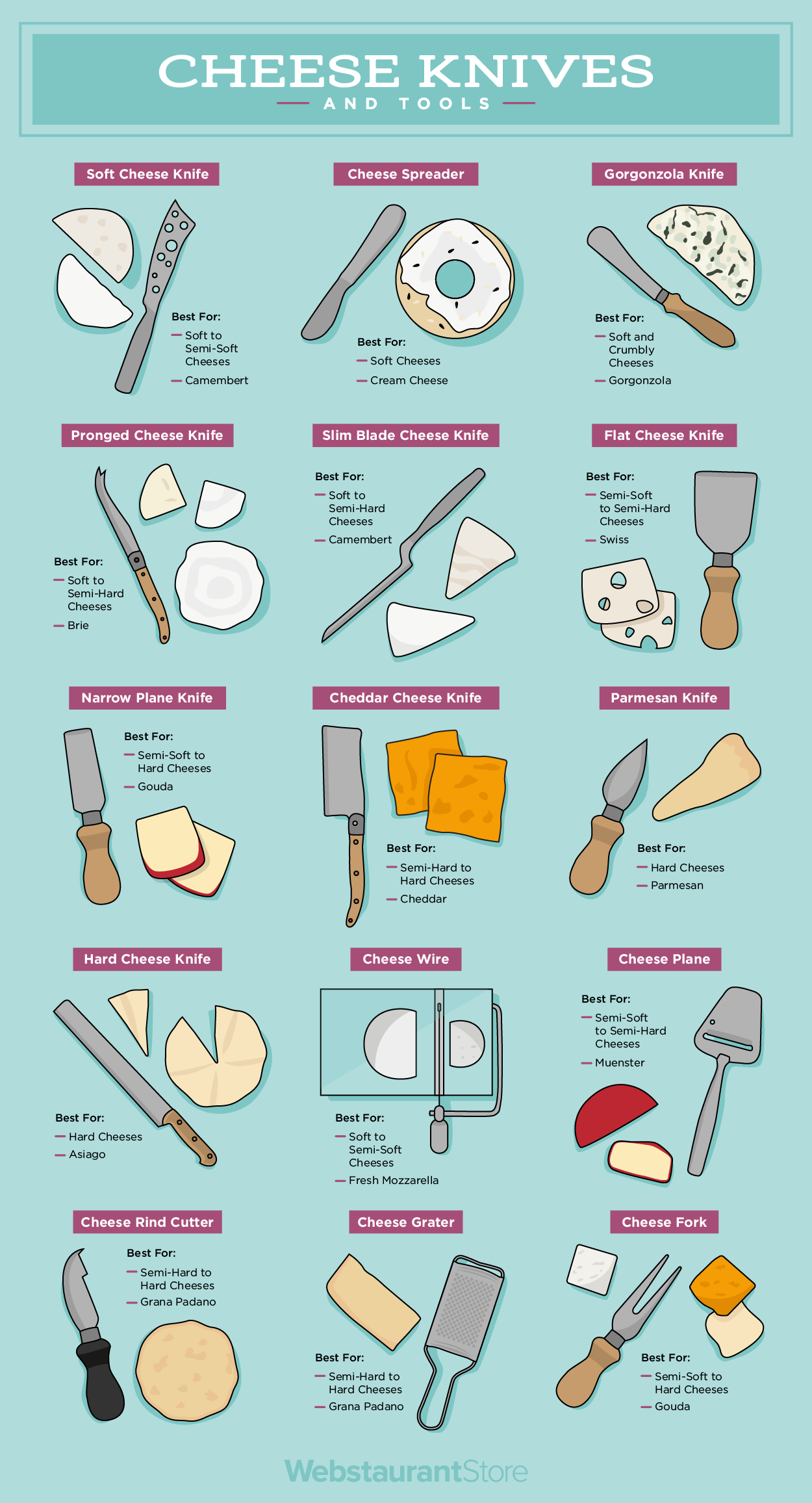

Just as it’s possible to lay out 8 different kinds of forks, 3 knives, and a multiplicity of spoons at a fancy meal, each with its own specified function, it is possible to put out multiple kinds of cheese knives. The reality is, if you’re putting out a board for your guests to serve themselves…well, unless everyone you know is a great cheese enthusiast, virtually no one will know one from the next and everyone will use whichever knife comes to hand to cut whichever cheeses they want.

My pragmatic recommendation is to keep a paring knife at the soft-cheese end of your board, and a larger, sturdier knife at the hard cheese end. It cuts down on the number of times you get brie (and the mold spores it contains) smeared across your pecorino. You might also choose to keep a blue on a separate board with its own knife, as blue molds are even more aggressive. Of the knives in the graphic below, the one that I’ve found that is genuinely better for its purported function than the general-purpose knives one normally has in the kitchen is the Soft Cheese Knife. Because there’s less surface area for the sticky paste to cling to, it slices in and out neatly and doesn’t tear up the little wedge you’re trying to cut in the process.

And be sure to listen to Episode 12 for suggestions on what to put on your holiday cheese board. Just make sure there’s room left on the board to cut the cheese! Happy holidays.

It’s the time of year for rich foods and lavish spreads–and that means cheese! In this episode, we talk about the special properties of winter milk and what that means for late-season cheesemaking. And then how to choose cheeses for a memorable holiday cheese board.

Resources

Ep 3: Touring the Cheese Kingdom

Washed rind cheeses are popular across Northern and Eastern Europe, but their reputation for stinkiness had dire implications for their popularity in late-Victorian North America–and for North American cheesemaking as a whole!

(Re) Sources

The Science of Cheese, Ch. 8

Ep 2: A Leap Towards Immortality

Media

Photo: Frangelico-washed hazelnut cheese (Lisa Caywood)

Non-Curdverse music via Wikimedia:

“Natural Rinds” is a big banner, encompassing a wide range of semi-firm to hard cheeses–everything from Asiago, Beaufort and Cheddar to Pecorino, Roncal and Tomme. Here we talk about what goes on inside the rind, and why it matters what’s on it.

(Re) Sources

Summer is prime cheesemaking season in much of the northern hemisphere! In this episode we talk about milk seasonality, transhumance–and pigs!

Sources and resources

Ep 5: Cheeses of the Season – Spring

Kingdom of Salt: 7000 Years of Hallstatt, Kern, Kowarik, Rausch and Reschreiter, eds; 2009

French Salers Production Halted Due to Drought

Read about modern transhumance practices in the Swiss Alps

Read about transhumance practices in the Caucasus

Image: Tête de Moine cheese with girolle, source Wikimedia