In Ep 13 on Cheddar, I mentioned bandage wrapping a few times in passing, but I found out from Twitter discussions that there are plenty of folks who are unfamiliar with the technique, since it’s something one only very rarely sees on package labels, and even then, there’s nothing resembling a “bandage” in evidence when you buy that piece of cheese.

With bandage-wrapping, you sort of make a mummy of your cheese: smear a layer of fat on the rind–originally whey butter, then later suet, now some folks use vegetarian options like palm or even Crisco. I like to use bacon grease, as it’s something we always have a lot of and it adds a wonderful, subtle, smoky flavor to the cheese. Then add a layer of cheesecloth and press it into the fat. Repeat two to three times more.

If you’re familiar with confit, you’re probably aware that fat can be used to seal off meat from oxygen and unwanted microbes that might otherwise grow on the surface of the meat. It’s the same principle here. The layers of cheesecloth make it easier to apply additional layers of fat since that’s harder to apply thickly on a freestanding thing like a cheese, vs meat that’s placed in a crock and surrounded w/liquid fat. The cloth is breathable, so it allows for some passage of air & moisture (waxed cheeses get much less), but cloth & fat combo greatly limits the exchange. That in turn limits how thick the rind of the cheese gets, which is important in a cheese that will age for a long time: you get more edible cheese if you don’t have a thick, dry rind. At the same time, it slows the surface aging, while allowing the interior to ripen slowly.

You don’t get as thick and dry a rind because less moisture is able to evaporate through all that coating. And that’s important in regions where the climate is relatively dry–especially if it’s also warm–because it prevents the rind from cracking. Cracks in your rind let in molds and sometimes also insects, if you’re an 18th or 19th century cheesemaker aging your cheeses in a barn or cellar. And those are bad news.

Cracking is less likely to happen if the cheese is almost evenly dry all the way through–think of the really hard cheeses from warm, dry climates like Parmesan or Pecorino. But Cheddar was designed to be a softer, moister, more toothsome cheese–and it was originally designed for shipping in the cool, damp climate of the North Atlantic. But New England gets hotter and drier in summer and colder and drier in winter than Britain–and already in the 1700s New England cheesemakers were shipping their wares to the much hotter climes of the mainland southern colonies as well as the British colonies of the Caribbean. So protecting the rind was critically important.

By contrast, you don’t get cracking if the cheese is kept in a cool, humid place–but you do get mold growth. And this is the other big attraction of bandage-wrapping: it limits mold growth on the rind of the cheese. So bandage wrapping has advantages no matter what sort of climate your cheese finds itself in.

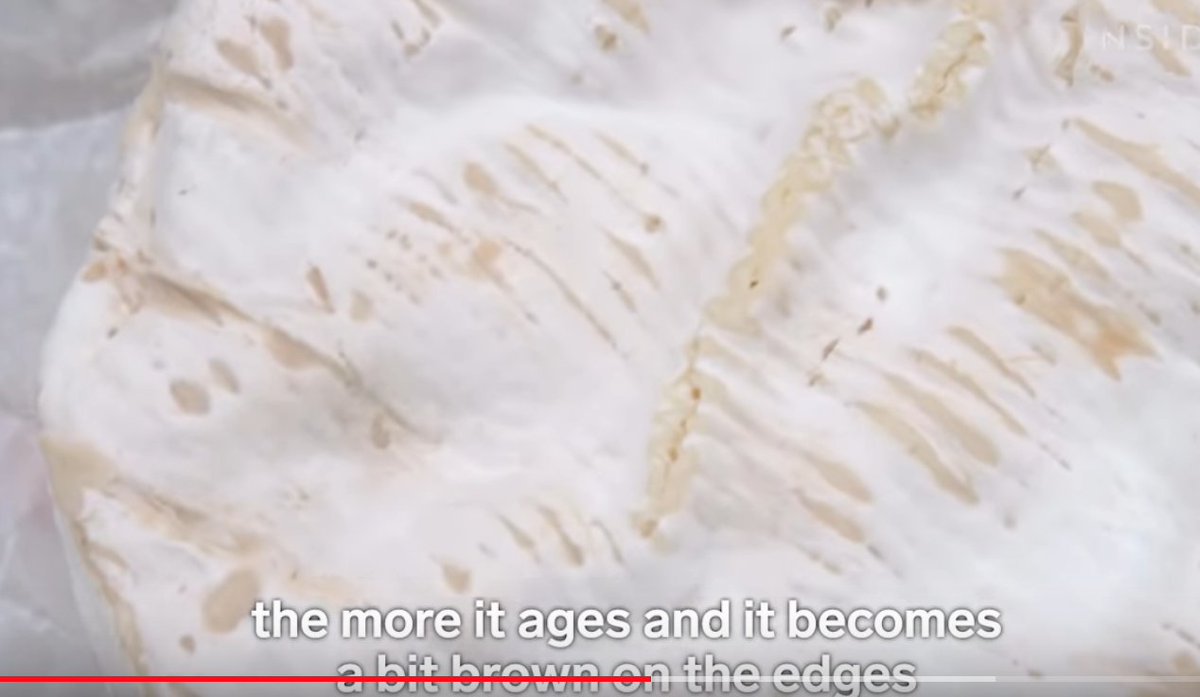

Many types of cheese make a virtue of mold, with cheesemakers encouraging certain types of molds and erasing others. The yeasts and molds on a rind get their sustenance from the cheese itself, and as they process those cheese nutrients, they also contribute to the slow breakdown of fat and protein in the cheese, which changes the texture, and also produces various esters and ketones that provide more complex flavors and odors to the cheese.

A skilled affineur, or cheese ager, knows how to develop and maintain a certain mold profile on a consistent basis. But still, these are wild, living organisms; the composition of the milk and therefore the organisms’ diet changes through the seasons; and there’s always subtle variation due to a variety of factors.

Subtle variation is the mark of a well-made artisan cheese. Wild, not-well-controlled variability is a manufacturing problem. And because skilled affineurs and just-right aging environments are somewhat rare and expensive, not having to carefully tend a rind is a big advantage in making an affordable product at scale–which was the primary goal of cheddarmakers almost from the very beginning.

This picture is courtesy of the head affineur at Rennet and Rind, a British affinage house. It’s a fantastic closeup of a bandage-wrapped cheese. But all that grotty-looking mold on the bandages…pretty much stays on the bandages. When you peel them off at the end of aging, you’ll have little to no mold on the thin rind, and a very clean-looking cheese.

Originally tweeted by IntoTheCurdverse (@curdverse) on February 6, 2023.