In Episode 2, I mentioned that the milk that most of us get from the supermarket is a highly engineered product, distinctly different from what comes straight from an animal in many ways. Here I’m going to explain what I meant by that.

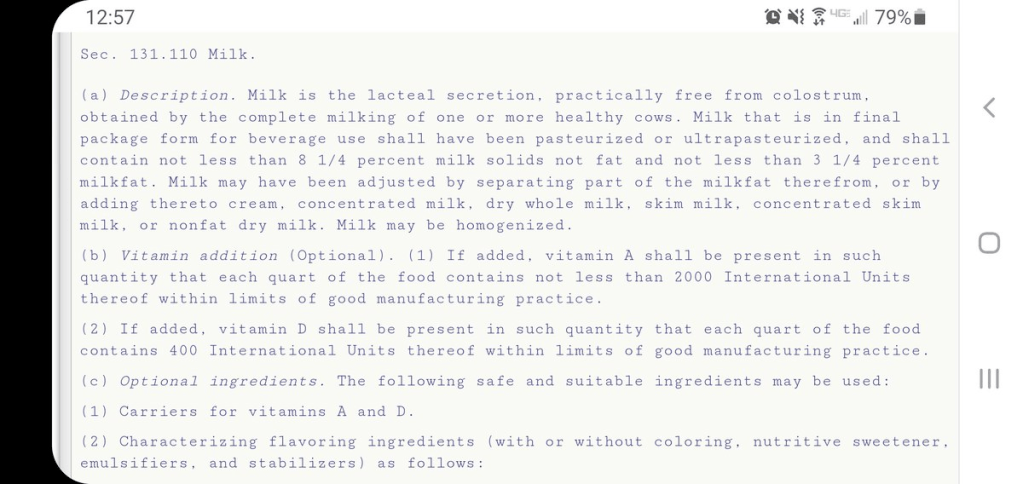

The first thing to know is that whole milk isn’t just whatever comes out of a cow, and maybe pasteurized. Take a look at the US FDA definition of “milk”:

Milk in the US must have a minimum of 3.25% fat and 8.25% other solids (proteins, vitamins and minerals, etc). These standards vary by country. The fat percentage in particular is higher in many countries, usually 3.5%. If you’ve ever wondered why US milk doesn’t seem as creamy as elsewhere, now you know why. US producers are allowed to skim more cream from their milk and still call it milk.

But milkfat content naturally varies a lot in milk. It varies by animal breed, by stage of lactation cycle, by season, quality and type of feed, and of course individual animals vary. So the other part of the definition allows the processor to adjust the actual levels in the milk on hand with various other dairy additives. If the levels are too low, they can add extra cream and other milk solids. There’s no maximum limit, but if things are significantly above required levels, processors may skim off more of the fat, since cream gets a good price on its own.

This balancing of milkfats and solids to predefined levels is called “standardization”. The milk we buy in the supermarket–even if it’s “cream top” or non-homogenized–is almost always standardized. On the other hand, if you buy milk directly from a farm or a very small producer, it may be pasteurized–heated to a specified temperature for a certain period of time–in order to kill all the microbial content of the milk, but it may not be standardized or homogenized.

In recent years, liquid milk producers seeking to capture the growing “premium” segment of the market for the sake of better margins, have started to offer non-homogenized milks. Sometimes they’re also organic, sometimes not. Lack of homogenization may indicate generally less engineering, but there are large producers who standardize and just don’t homogenize in order to capture the price premium that comes from the perception of their milk being inherently more “natural”. One “cream top” brand also pasteurizes at near-ultra pasteurization temps, which results in a flat-tasting milk which isn’t great for cooking with. (Never mind making cheese. As I found out the hard way.)

The largest share of the liquid milk market in the US is 2%, not whole milk. That’s what gets served in schools and most other government facilities, which are meaningfully large customers for large milk producers.

Cream separation for cow milk is done by centrifuge. This is different from homogenization, in which the milk is forced through a mesh, in order to cut the fat globules small enough to stay in solution. The temperature and speed at which the milk is separated drives cream density. Cooler and slower processes give manufacturing or “pastry grade” cream, which is typically ~46% milkfat. The cream in supermarkets sold to US consumers is typically in the mid 30%s.

Large producers are also sourcing from lots of different dairies with different approaches to feed, etc. They all get blended together and then processed as above. It makes for a very consistent product, but also one deliberately void of any distinct flavors or terroir.

By the way, if you’ve ever wondered about why there’s so much about Vitamins A and D in milk marketing, it’s because they’re fat-soluble vitamins. Remove milkfat, and you also remove vitamins. But since milk provided to schools has to meet the same nutritional requirements as whole milk, processors have to add those vitamins back by other means (“A and D fortified”). And when selling to the general public you want to explicitly tell your buyers that lower fat milks are still nutritious, but also don’t want to give the impression full fat milks DON’T have as much A and D, so they tend to be marketed on all milk types.

All of this, of course, is largely irrelevant for non-cow milks. They still meet the FDA minimums by default–goat milk is typically close to 4% milkfat and sheep 7-8% and non-fat solids are usually proportionally higher. And those milks are naturally “homogenized”, in the sense that the fat molecules in those milks don’t separate out easily. There aren’t nearly as many large dairies or processors of these milks, and the percentage of liquid milk vs other uses for those milks is also very different than for cow. The majority of goat milk in the US is sold to cheese manufacturers, and virtually all sheep milk, rare as it is, gets made into cheese.