Here’s a lovely video about how traditional Camembert is made, which very nicely illustrates a number of the things I talk abt in Episode 7.

One thing I didn’t specifically mention is that as with many cheeses, the AOP version must be made with milk from a specific breed, in this case the Normande cow. You can see some in the background at :13: mostly white with dark red splotches.

The Normande breed produces high protein, high fat milk–4.4% fat on average, vs 3.25-3.5% from the typical Holstein.

At 1:17 we get our first glimpse of the interior of a traditionally made bloomy rind. Unlike the stabilized paste cheeses typically available in supermarket, the texture is not even throughout the cheese. That’s because it ripens from the outside in.

At 1:35 the maker talks about the “croûte fleurie” of the cheese. That literally means “flowering crust”, referring to the fruiting of the geotrichum & penicilllium fungi on the rind. The slightly more indirect translation in English is “bloomy rind”.

Fun side fact for those who don’t speak French: that little “hat” mark over the U in croûte is called a circumflex, and it marks where there USED to be an S, which at some point stopped being pronounced in French, and then much later orthography caught up with pronunciation. We often have the same word, with the S, both in writing and in speech, in English: croûte = crouste = crust.

In the podcast I mentioned that most of these bloomies were originally farmhouse cheeses, things that didn’t require a lot of hands-on work that would tie down the farmwife (typically) as she ran around taking care of all of the OTHER business of running a farm & household. So a lot of these cheeses are traditionally made from raw milk that’s just left to sit around and acidify on its own for 12-24 hours. (Longer if it’s cooler, less time if it’s warmer.)

Some bloomies are entirely lactic set with very little rennet–many of the goat cheeses, and also Brie de Melun. Others, including most other types of Brie and also Camembert, get more rennet added (as at 2:29) for a bit more structure to the curd.

Note that the raw milk is never heated: it just comes out of the animal and is left to sit in buckets or forms as it acidifies. The French often categorize cheese by dividing them into “cooked” and “uncooked” cheeses for this reason, and then “pressed” and “unpressed”.

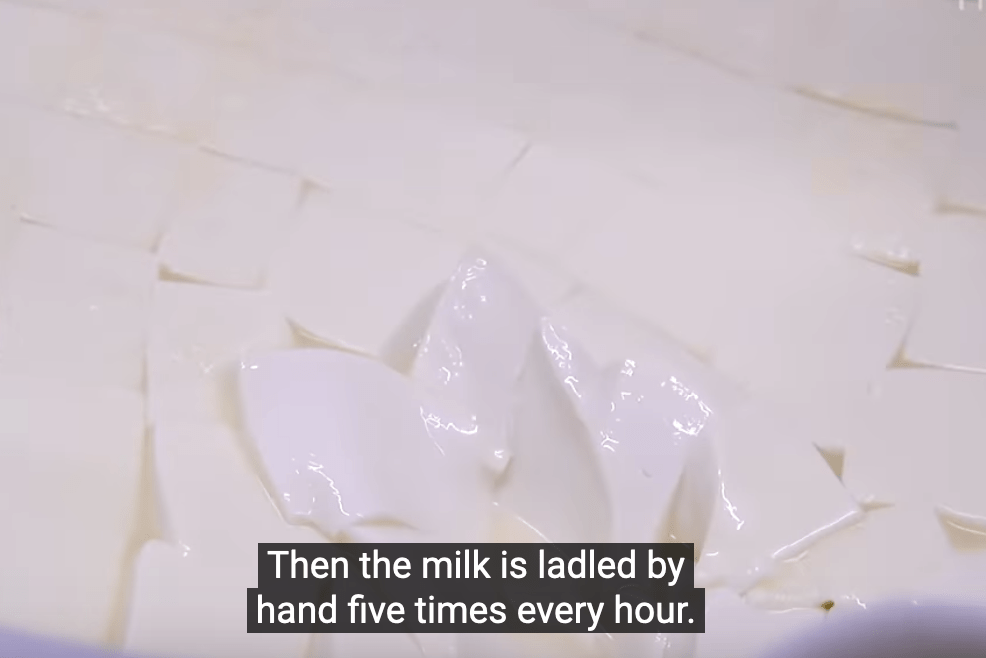

At 2:32 we see the curd being cut into quite large chunks. This allows the curd to retain a lot of liquid, which will help it break down quickly over a few weeks.

The curd is barely stirred, if at all, so it hardly retains its shape as it gets ladled into molds. As the maker notes at 2:42, each layer of ladling (one ladle per hour into each mold) condenses from a full mold into a thin layer over an hour, as the fragile curd blocks quickly collapse. Camembert molds are simply round cylinders with holes on the sides and no bottom. The whole goal is to allow the whey to drain out without any impedance.

Here you can see the curds collapsing and flattening as they shrink down into the mold.

In case you’re wondering, yes, a little bit of a skin does develop on the top of each layer during the hour between ladlings, as the top portion, exposed to the air, dries out a bit. At 3:33, the maker pulls on the sides of a day-old cheese to show how the layers can be seen. The cheese is unpressed other than with the weight of new curds being added on top of others, so they aren’t tightly knit together.

At this point it should become clear that this approach, while wonderfully low-key from the point of view of someone with a million other things to do in a day–18-24 hours to acidify, another 30-45 minutes to coagulate, 5 hours to mold, just stopping by every now and then and then going on about other business–is completely antithetical to mass production, where high throughput is king. So mass-market cheeses are made with lots of added cultures to jumpstart acidification; the molding/draining process is also done at a warmer temperature, so curds drain faster. It’s the opposite of “low ‘n slow”.

Around 3:45 they talk about the aging time, 4-5 weeks, which allows the fuzzy white molds (fungi, really) to grow in on the surface and then work their way into the curd. Here you can see cheeses a week or so old, when the rind is just partially grown in. It comes in patchily at first, then starts to spread until you get a fairly even coat.

The maker mentions at 3:57 that they add geotrichum and penicillium. Sometimes freeze-dried spores are added to the milk as it’s acidifying; in other cases, especially large productions, they can be added to brine that is sprayed on the surface of the cheese after it’s made. Because there’s less of the fungi active in the curd, this enables the producer to have a nice traditional-LOOKING cheese, but less outside-in aging, which would produce a less even texture.

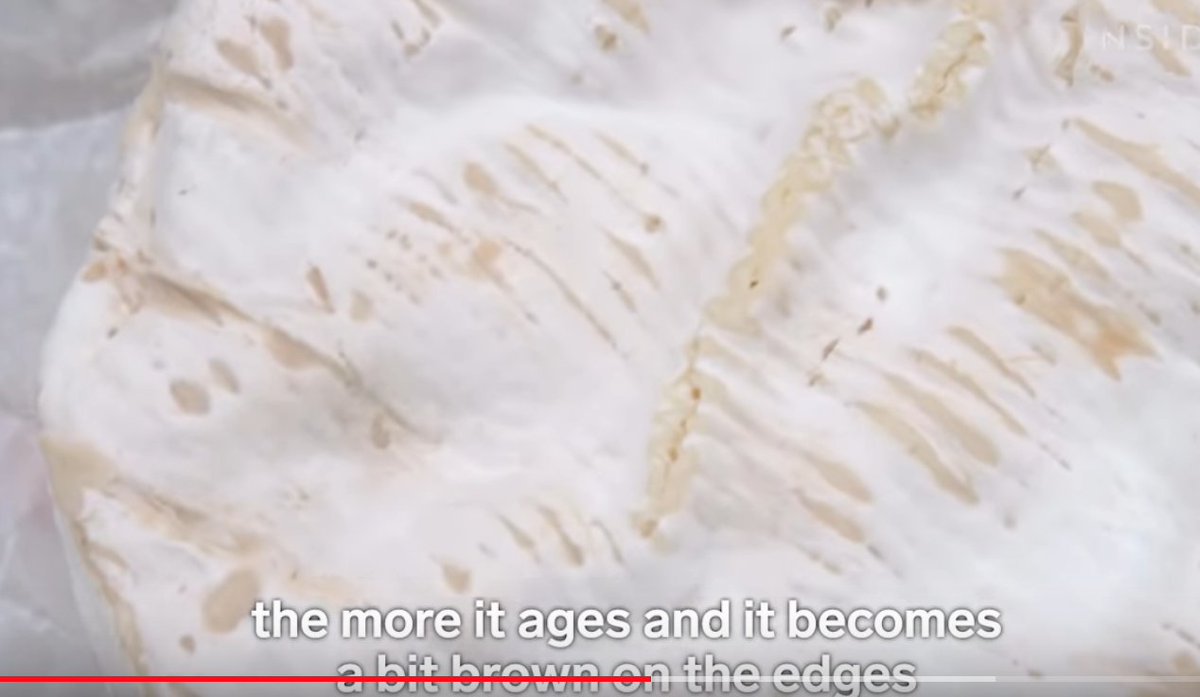

Towards the end of Ep 7 I talk about how to select a cheese in the supermarket. One thing to look at is the evenness of the rind. Some bloomies are sold, honestly, too young, and never really soften well in your fridge. Others, especially imported ones, are often older than ideal. You can decide for yourself what the sweet spot for you is, depending on how quickly you eat your cheese. If it’s for a party tomorrow, buy an older one. If you just have a few slices every few days, buy a younger one.

At 4:06, we see how in older cheese starts to develop “bald” spots, where a beige rind starts to show through.

At 4:10 we get a closer look at the inside of a traditionally ripened bloomy: crust about the texture of wet cardboard, oozing paste just inside it (called the “cream line”) and then a still-firm, cakey-textured center.

This is obviously quite different from the stabilized-paste bloomies we typically get in supermarkets. I talk about how stabilized paste is different in virtually every aspect of how it’s made towards the end of Ep 7.

So if you see something with these multiple textures, you’re getting a cheese made fairly traditionally–but you’ll want to eat it quickly. If it’s uniformly firm, with no “squish”, it’s a stabilized-paste and either extremely young, or one of the brands that never really softens.

Around 4:33 the maker talks about the traditional wooden box in which Camemberts are often sold: it helps the cheese keep its shape as it softens and ages, and protects it from getting squished during transport.

A number of soft-ripening cheeses are packaged this way, in fact…St Marcellin, a bloomy with a very thin rind, is often packed in small ceramic pots because it gets runny so easily.

Livarot, another Norman cheese (washed rind, not bloomy) that’s probably older than Camembert, is taller and traditionally tied twice around with raffia to help it hold its shape.

Around 7:11 they mention that most of the Camembert made today is made with pasteurized milk. Only ~10% of Camemberts are made the way we’ve just seen, with raw milk. Because of the very long production time for the traditional approach the AOP label is extremely important commercially for small, traditional producers–it allows them to differentiate their product and maintain a price premium that allows them to stay out of the red financially.

The label, however, is a subject of much controversy, as the government has broadened the label in different ways several times. Here’s a discussion of one of the more recent contretemps…which, because it’s France, led to protests that included traditional Camembert cheeses being dropped in MPs’ letterboxes.

All of this is neither here nor there for those of us in the US, since 4-5 week old, raw milk cheese can’t be imported here. But if you’re touring around France, enjoying Euro-dollar parity, you may wish to look for “fermier” on the label in a proper cheese shop to get the full flavor experience of a traditionally made Camembert.

Originally tweeted by IntoTheCurdverse (@curdverse) on July 17, 2022.