There’s an old tale going around a lot this week, in which shepherds abiding in fields keep watch over their flocks by night. Very old tale: humans have been doing that for some 11-13,000 yrs, first for meat, then wool, then milk. The only animals w/whom we have an older domestic relationship are dogs.

You know where this is going…cheese. Yogurt is part of this thread too, since it’s what inspired a lovely article (to follow) which explores dairy in Eastern Turkey–the westernmost part of the Fertile Crescent region where domesticated sheep were developed. It’s about the hometown of Hamdi Ulukaya, the rags-to-riches founder of Chobani yogurt. In his hometown, of course, yogurt is made from whole sheep milk. so ~8% milk fat. Rather different from what’s Chobani makes in the US.

You really should read the whole article, if only to travel to someplace you may never go, and read about things that may soon disappear: notably the local cheese, which has been made pretty much the same way for millennia. But there are a few passages I wanted to highlight.

First, the fact that milk is actually a seasonal product, just like cherries & tomatoes. I’ve highlighted that in each of the Cheeses of the Seasons episodes, but it’s quite easy to forget for urban dwellers for whom milk is always just there, seemingly always the same. The authors of the article were unaware of that before visiting the town. =)

Cows lactation cycle is quite long, typically ~300 days, and modern domesticated cows are not strongly seasonal breeders, with both reproduction and milk production being a matter of nutrition–this is partly why in cow-centric countries, milk seems eternally available. Sheep and goats are much more strongly seasonal, like their wild counterparts, and while modern science has made it possible to manipulate these cycles somewhat, their lactation cycles usually run 6-8 months for dairy breeds, less for non-dairy breeds.

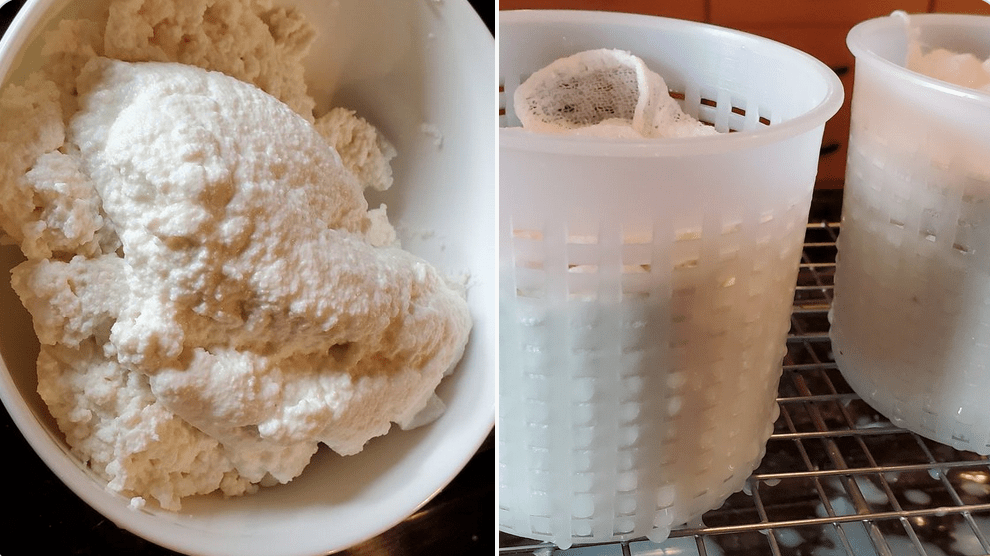

Natural reproduction cycles for sheep and goats align very closely to natural feed availability. If you or your partner have ever nursed a baby, you know that milk output is minimal for the first 2-3 months, then kicks into high gear and mom is ravenous. Same for dairy animals. Babies are born in early spring; early milk production is powered primarily from mom’s own fat stores, augmented w/dried fodder and the first fresh grass. Just as babies start getting really hungry, pastures are full of mature grass. In the fall, as grasses dry and die, herds are traditionally culled, babies weaned and everyone goes on dry fodder again. Moms’ teats get a rest, and the cycle starts again. This brings us to a traditional method of cheese production: cheeses are made in-pasture, right after milking. In Europe, this in-pasture style of cheesemaking is called “alpage”, a designation you’ll see on some gruyere & other alpine cheeses.

The milk is heated a bit during the cheesemaking process, but only some are heated to high enough temps to be counted as pasteurized. Most are raw milk. And here we come to conflicts between traditions and modern regulations.

You’ll notice, in the above quote, another common element of dairying: gendered tasks. In western Eurasia, it’s common for men to look after live animals and for women to process the milk. So much so that cheesemaking and witchcraft–another heavily gendered activity–have long been linked in western folklore…

About that goatskin in the previous quote: the local cheese, “tulum”, was traditionally aged not in caves but in animal-skin bags, which are much handier when you’re doing alpage cheeses while moving about in the mountains. Like any skin, they’re somewhat porous, allowing excess moisture to escape the curds and a regular flow of air to reach them. No doubt the authorities will have problems w/that too, even if the pasteurization issue gets resolved.

But there’s one more problem: that part about watching over their flocks by night:

Sheep have changed a lot in the millennia since humans started rounding up mountain sheep–their shape, their size, how much wool and milk they produce. But their natural cycles–and those of their predators–have not. And our natural biorhythms haven’t either. In an era when there are many ways to earn a living that don’t involve staying up all night outside in the cold, human preferences tend to win. Back 2000+ yrs ago, when animals meant livelihood, even wealth, the sacrifice of a lamb to unseen powers was significant. It’s why it was embedded in rituals of many West Asian religions.

We’ve now mostly given up that form of sacrifice in the West, but you can still appreciate the work of all those shepherds, ancient and modern: if you’re thinking in terms of lambs this week consider partaking of some of their cheese. Here are a few suggestions to get you started:

Best Cheeses 2019: Sheep’s Milk – culture: the word on cheese